By Tom Slater and Tom St. Amand

By Tom Slater and Tom St. Amand

The disturbing success of U-Boats early in World War II forced the Allies to produce an effective anti-submarine vessel to protect their merchant ships in convoys.

Using a whaling boat's familiar design, an English boat building company created the corvette. Not everyone was impressed.

Upon seeing one for the first time, a British admiral remarked, “My God! Since when are we clubbing the enemy to death?”

Despite their appearance, corvettes became the backbone of the Canadian navy. That corvettes were not designed for lengthy ocean crossings through fierce storms mattered little. With their 200-kilogram depth charges filled with high explosives, their durability in rough weather, and their ability to out manoeuvre a U-boat, corvettes were indispensable as ocean going escorts.

Unfortunately, between 1942 and 1944, four local sailors — Alfred Kettle, William Anderson, Michael Paithowski and Wallace Horley — died when U-boats sank their corvettes while they were on convoy duty.

The threat of U-boats notwithstanding, daily life aboard a corvette was often miserable.

Constant seasickness, even among the most seasoned sailors, left men retching and moaning for hours. The corvettes' rounded hulls caused them to ride atop the seas, rather than to dig into the waves. In rough weather, corvettes climbed the crests of mountainous waves like a floating cork, only to make a stomach-shuddering and bone-grating plunge into the troughs before rising with the next crest ad nauseam.

Winter was worse because sailors had to keep their ship from icing up. As the heaving water sprayed their ship and froze to anything made of metal, the danger was that the extra weight could keel the boat over.

So a sailor like Petrolia native Alfred Kettle, Chief Petty Officer aboard the HMCS Spikenard, joined his fellow crew members on their “turn to” (getting to work) and used hammers, axes, crowbars and even their fists to chip the dreaded ice away. All this while waves continued to pummel the hull and to soak the men on the deck.

Two Sarnians were aboard the HMCS Shawinigan: William Anderson, the ship's Leading Coder, and Petty Officer-Stoker, Michale Paithowski.

The Shawinigan's open decks, combined with being so close to the water level, meant every crew member was often cold and always drenched.

Corvettes were known as the “wet ships” for good reason—as the seas broke over the decks, salt water seeped through the seams, hatches and ventilators. Foul smelling water was inescapable, eventually making its way into every compartment of the ship. Usually the crew just wore their clothes wet until they dried in the wind: they had no other choice.

Like other corvettes, the Shawinigan had an infestation of cockroaches; little fresh water to wash, causing a nasty rash called “sailor's skin”; and scant servings of mould-free food.

Her crew of 91 men was cramped and crowded. The corvette's mess decks were the areas allocated for living, sleeping, eating and relaxing off duty and men slept in canvas hammocks three deep that hung from every conceivable spot of the deck head.

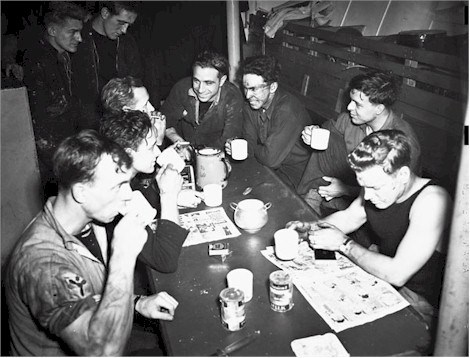

Despite the gruesome living conditions, crew members like Sarnian Wallace Horley, 22, a stoker aboard the HMCS Alberni, formed a tight bond. To maintain their spirits, the crew sang songs, composed limericks, exchanged stories and jokes, played ongoing poker games, and pulled practical jokes on one another.

Sailors looked forward to two daily treats: their beloved “kye”, a viscous hot drink made from a block of coarse chocolate, scoops of sugar, and canned milk; and, for those over 21, a 2.5 ounce ration of “grog”, rum mixed with water or Coca-cola.

In fact, most crew members aboard the Alberni were getting ready to enjoy their noontime ration of grog when the stealth sub U-480 approached undetected and sank her in the English Channel in August 1944.

Some called the corvette a “humble warship.”

Men who served on a corvette in WWII had to be tough, durable, and resilient, much like the ship herself.