George Mathewson

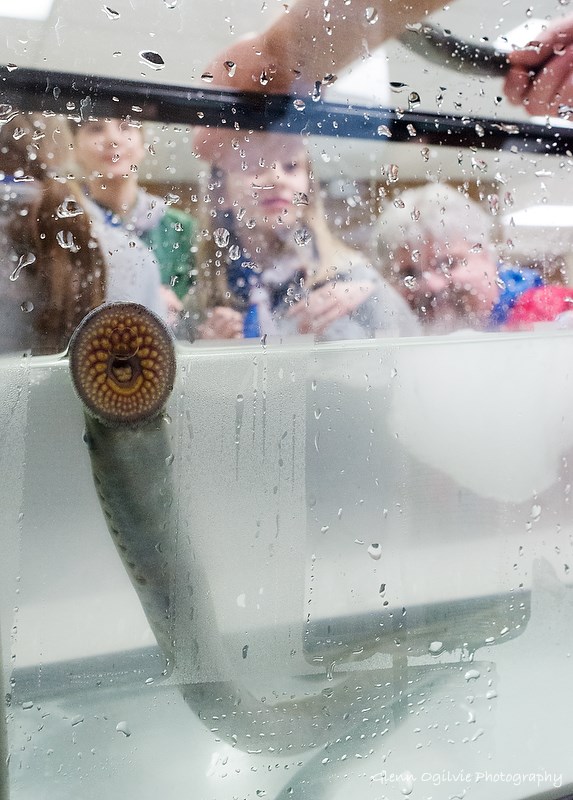

The eel-like thing squirms as it’s lifted from a water tank before fixing its sucker mouth to the bare arm of Jim Campbell, a community liaison officer in Sarnia with Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

It looks like a monstrous leech on steroids, but with sharp teeth, and the 24th Dunlop Scouts and Cubs are fascinated - and horrified.

“Nothing makes an impression like a live sea lamprey,” says a chuckling Paul Sullivan, division manager of the Sea Lamprey Control Centre in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont.

“They predate the dinosaurs and have been on Earth more than 300 million years. To have survived this long they must be doing something right.”

The demonstration at Dunlop United Church using live lamprey from Lake Huron came with a message - that vigilance is needed to protect the Great Lakes.

The sea lamprey is a primitive, eel-like fish that first turned up in Lake Erie nearly a century ago, making it the prototypical alien invader.

Before people worried about zebra mussels and Asian carp, sea lampreys had already decimated fish stocks so dramatically that it led Canada and the U.S. to form the Great Lakes Fishery Commission in 1955.

“What we’ve learned is that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” Sullivan said. “Once an invasive species is established it takes an Herculean effort to maintain that species at low levels.”

Though originally from saltwater, sea lamprey have adapted to living entirely in the fresh water of the Great Lakes.

Adults attach to hosts with suction-cup mouths and dig their teeth in for grip, then feed on the fish’s blood and body fluids.

At least half of attacks are fatal and a single adult lamprey will kill an average of 18 kilograms (40 pounds) of fish.

Though sea lamprey are here to stay, barriers, traps and chemical lampricide applied to rivers and streams in which they spawn have cut populations by 90%, Sullivan said.

“They are highly adaptable and highly resilient to change … It’s an ongoing battle.”