Phil Egan

Seventy-seven years ago this week 4,963 courageous Canadians probed Hitler’s “Fortress of Europe” in a raid that presaged the massive assault on Normandy to come in 1944.

It happened on Aug. 19, 1942 and was known as the Dieppe Raid.

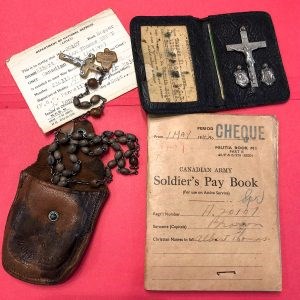

Among the Canadians troops that sailed from Sussex, England to France on the previous evening’s tide was a 20-year-old Sarnia sapper with the 11th Field Company of the Royal Canadian Engineers. His name was Al Brown, and in his pocket was a rosary in a little black pouch.

“When you go into action,” his father had told him, “take your rosary with you and you’ll be protected.”

Brown clutched the rosary and prayed as his landing craft approached the beach, and bullets whistled as he ran for cover whispering “Hail Mary’s.” The heel of his boot was blown off.

But others fared far worse. The raid was a disaster, and 900 Canadians were killed and thousands lay wounded on the beach.

Al Brown was part of a seven-man team attached to the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry charged with demolishing a reinforced roadblock in the Dieppe’s centre. But the mission failed when three squad members were lost, including the soldier with the fuses and detonators.

Taking shelter in a theatre opposite their objective, the Canadian engineers soon found themselves under advancing friendly fire. As the battle against the Germans raged, a Canadian tank began firing armour-piercing shells at the theatre.

Scrambling to the top floor, Brown and the remaining sappers were desperate to alert the Canadian tank they were countrymen, not the enemy. Shoving Brown’s battle tunic on the end of a broomstick, a soldier began frantically waving the familiar garment at the tank driver.

The tank ceased firing, but the battle tunic slipped and fell three storeys to the street below. German troops firing machine guns stormed the theatre and Brown and another soldier were captured.

The battle around Dieppe raged for another nine hours. When it was over, a girl named Angel Pointereau, who was watching from a nearby window, crept into the street and retrieved the Canadian battledress tunic. Fearing German retribution should it be discovered in a French home, Angel’s mother buried the rosary and other articles removed its pockets and threw the tunic back into the street.

After the war, Angel recovered the buried artifacts and took them with her when she travelled to Paris to open a hairdresser’s shop. For her, they were relics of the day Dieppe would never forget.

Al Brown spent the next 29 months as a prisoner-of-war. Freed in 1945, he returned to Sarnia to become a Polysar process operator.

In 1970, a woman from Montreal was having her hair styled in Angel’s hairdressing shop in Paris. Hearing the tale of the soldier’s lost rosary, she offered to return it to Canada and try to repatriate the lost articles. The Royal Canadian Legion tracked Al Brown to Sarnia.

In 1977, some 35 years after his battle tunic fell to the streets of Dieppe, Al Brown returned to the city to meet the “Angel” who had saved his rosary.

Angel spoke no English. Al Brown spoke no French. But he embraced her on the rebuilt streets of Dieppe and gave thanks for her simple act of kindness.

Memorial honours Canadian engineers at Dieppe

Phil Egan

“Freedom and independence,” Sarnia’s Al Brown told a memorial service on Aug. 24, 1980, “are sustained by those who place love of country above love of self.”

The gathering was at a three-year-old memorial in Newhaven, Sussex, erected to honour member of the Royal Canadian Corps of Engineers who had left the port 38 years earlier to fight and die at Dieppe, France.

Al Brown, 56, knew of what he spoke. He had raced across the pebbly stones of the city’s beach cradling sixty pounds of explosives in his arms before being taken as a prisoner-of-war.

Broadcast journalist and author Tom Brokaw christened these men “The Greatest Generation” in his 2004 book of the same name. They came of age in the hard times of the 1930s, were tempered by the call to King and Country in a perilous war, and returned from battle, if they were fortunate, to build a buoyant post-war economy and raise their families.

Al Brown, father of retired police officer and current Crime Stoppers coordinator Tim Brown, was one of the admired ambassadors of that celebrated generation.

Following the war, as secretary of the Association of Royal Canadian Engineers, it was Al Brown’s correspondence and work with the Newhaven town council that was largely responsible for the construction of the memorial at the English seaport dedicated to the fallen engineers of Dieppe.

We proudly remember him and his “love of country above self.”