Cathy Dobson

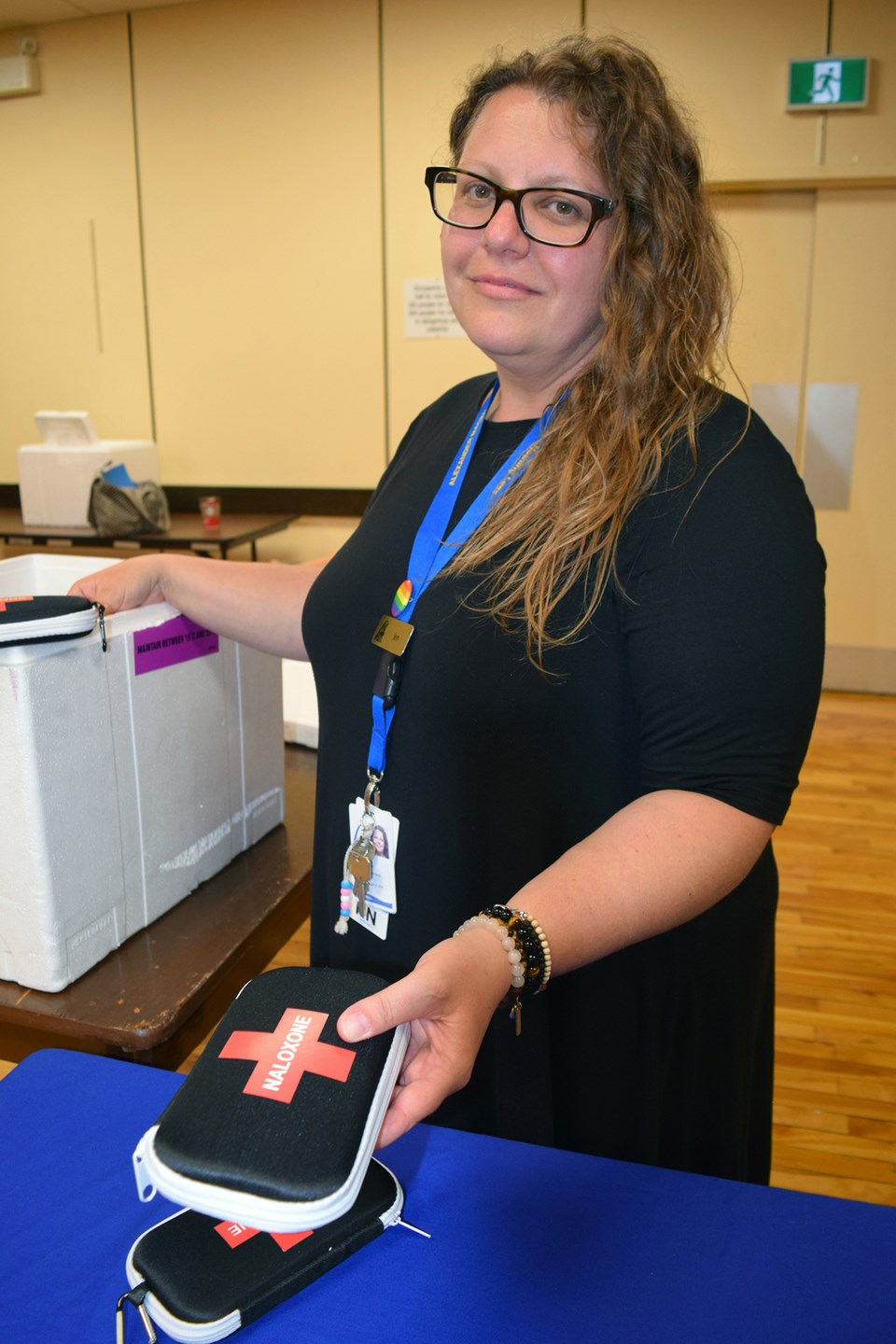

With opioid abuse escalating in Sarnia, those on the front line are urging residents to have a life-saving Narcan kit and know how to use it.

“Overdoses are happening on our streets every day and we need people calling to tell us,” Sarnia Police Sgt. John Pearce said at a unique public forum that attracted more than 100 people last week. Pearce heads Sarnia’s drug unit.

“These people are unconscious and they will die within two to five minutes if you don’t get to them,” said Pearce, who heads Sarnia’s drug unit. “Timing is critical.”

That’s why he and other panelists want as many as possible to be equipped with a free Narcan kit. It contains naloxone hydrochloride in the form of a nasal spray that temporarily blocks opioid effects.

Sarnia’s opioid problem may have started with prescription drugs but pharmaceutical drugs are not the issue now, said Pearce.

“We don’t see Percocets, oxys or fentanyl patches on the street anymore. Fentanyl powder is the new problem. It’s being mass produced in other countries and imported here and it is completely illegal.”

A very small amount of fentanyl powder, the size of four grains of salt, can kill, he said.

Educating the public about Narcan kits and how to use them if an opioid overdose is suspected is the current strategy to combat opioid deaths, according to the panelists from Bluewater Health’s emergency department and addiction services, Lambton EMS, Lambton Public Health and Sarnia Police.

All emphasized the importance of remaining with an overdose victim to administer naloxone, call 911, and provide critical information to responders.

“Help us save that life,” said Nadine Neve, manager of emergency services at Bluewater Health.

“Don’t drop someone and leave. We don’t call the police. All we’re focused on is saving that life.”

The panel assembled at the Unifor union hall at the request of Sgt. Pearce and Laurie Hicks, a local mom who lost her 25-year-old son, Ryan, to an opioid overdose in 2015.

“Four years ago, we didn’t know what a Narcan kit was or that you need to stay with someone if they are overdosing,” Hicks said. “Either of those things could have saved my son’s life.”

She works tirelessly to stop more opioid deaths in Sarnia and wanted to hold a forum so the community can better understand addiction.

Hicks said she wants to get the correct information out there because she sees so many myths spread on social media.

“I also believe that we all should carry a Narcan kit. You never know when you’ll save a life.”

Hicks said strong attendance at the public forum reflects the community’s deep concern about opioids.

“It’s hitting everybody,” she said.

More than 700 Narcan kits have been handed out by Lambton Public Health so far this year, said Ellie Fraser, mental health and addictions program co-ordinator.

“And that doesn’t include what the pharmacies are handing out.”

There’s growing evidence that so-called bystanders at overdose scenes are taking positive action, said Tim McIntyre of Lambton EMS.

In April, 12 bystanders gave naloxone to someone with an overdose, he said.

A key piece of legislation called the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act is helping to keep bystanders from leaving the scene, said Pearce.

The Act ensures that people who call police for help will not be arrested.

“It’s geared toward criminals who are afraid to call 911 because there are drugs in their house or they just gave the drug to the victim,” said Pearce. “When we roll up, we want you to stay. We won’t be judging you.”

While much of the forum was about Narcan kits and stemming the number of opioid deaths in Sarnia-Lambton, several people also wanted to talk about the damage the drug culture is having on their neighbourhoods and personal property.

“It feels like there’s no light at the end of the tunnel,” said one distressed man.

There is hope, countered Paula Reaume-Zimmer, vice president of mental health and addiction at Bluewater Health.

“We have witnessed extraordinary change with individuals who have made a commitment to change.”

The community is still waiting on approval for a 24-bed residential facility for those suffering with drug addiction in Sarnia, she said.

The Ministry of Health was expected to make a final decision last year but there’s been no update for months.

“It’s difficult to give any explanation.”