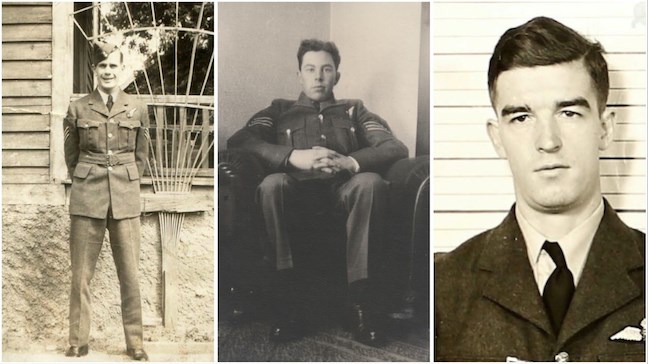

Any member of the elite Pathfinder Force in WWII knew that if he survived 12 missions he was beating the odds. Unfortunately, luck was not with Sarnians Gordon Fordyce, Curtis Goring, and Charles Nash, three members of the Pathfinder Force who died in action.

When the war began, RAF Bomber Command was Britain’s only means of taking the fight into Nazi Germany.

The British needed to destroy German factories and industries that housed the raw materials used to build their weapons, tanks, planes, and ships. In May 1940, when the Luftwaffe destroyed Rotterdam and the Netherlands surrendered, the British took note. If they did not inflict damage on targets in the Ruhr Valley, Germany's industrial heartland, Hitler's formidable war machine would be unstoppable.

Their hopes lay with Bomber Command, but the airmen faced daunting challenges. Key targets in occupied Europe and Germany were heavily defended and daylight raids became suicide missions. The RAF moved to night bombing, but they became hit-or-miss sorties—emphasis on the miss. Nearly 50% of their bombs landed in open fields.

Their inaccuracy was inevitable given the primitive technology available for night navigation early in the war. To estimate an aircraft's position in relation to its targets, a navigator climbed into a Perspex bubble atop the aircraft, took a half-dozen timed photos of the stars and then consulted navigation charts. He also had to calculate the speed of both the wind and the bomber.

An examination of bombing missions in 1940 and 1941 confirmed that, at best, only one in three British bombers got within eight kilometres of its target. And RAF bomber crews, which included many Canadians, were still dying faster than they could be replaced.

But as the Germans continued to build more fighter planes and flak guns, the British fought back.

Early in 1941, the RAF introduced larger four-engine bombers that flew farther and carried a heavier payload. Twelve months later, they began using GEE, an improved radio navigation system which allowed bombers to navigate along an arc in the sky. They also launched larger bomber attacks—the May 1942 raid on Cologne featured the first thousand bomber attack.

And in August 1942, the RAF employed what some military experts still consider the most important innovation in bombing missions: the Pathfinders.

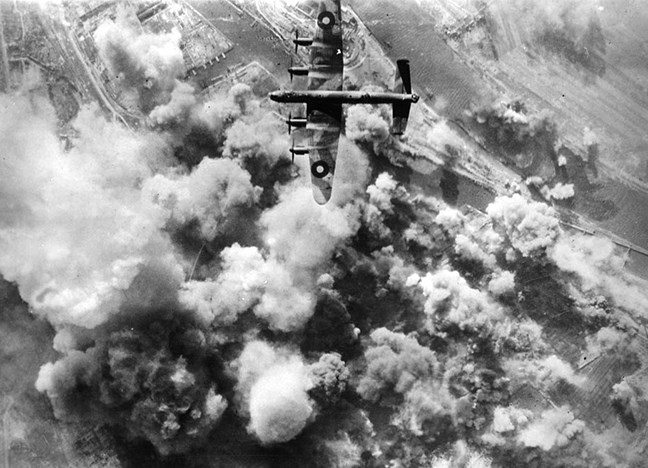

The Pathfinder Force had a vital role, so Bomber Command selected only the most competent airmen from existing crews. Spearheading the bomber stream, the Pathfinders' assignment was to locate and then to fly over enemy targets a few minutes before the main force of bombers arrived. After identifying the targets, they dropped coloured flares to pinpoint targets and to illuminate the path for the follow-up force.

When the bombers arrived minutes later, their crews flew between the coloured flares, knowing they had much better odds of hitting their targets. And within the main force itself were other Pathfinders that continued to mark enemy targets with flares as the bombing continued.

The Pathfinders' contribution was incalculable. They drastically improved precision bombing on key targets, reduced Germany's industrial output, and allowed the Allies to conduct even more bombing missions. The Pathfinders were so effective that they forced the Germans to divert thousands of their men and weaponry from other fronts into fighting Allied bombers.

These elite crews understood the many inherent risks. They arrived first, vulnerable against enemy night fighters and anti-aircraft guns that awaited them. If they were “coned”–meaning they were caught by multiple enemy searchlights – they were often shot down. Equipment failure and mid-air collisions were constant threats, along with being bombed by their own planes.

Little wonder that Pathfinders received an immediate promotion in rank and a pay raise – ”danger money” it was called. They earned every penny if they lived but, sadly, many did not. In all, over 3,600 Pathfinders died in action, including Sarnians Gordon Fordyce, Curtis Goring, and Charles Nash.

“He never came home”

All three men were in their 20s and single when they left Sarnia to enlist with the RCAF. Each eventually joined the Pathfinder Force with tragic results.

Beginning in mid-June 1943, WOII-Pilot Gordon Fordyce flew 21 missions with RAF #12 Squadron before he joined the prestigious Pathfinder Force.

He lasted three missions.

On November 23, 1943, Fordyce's Lancaster was part of RAF #156 Squadron that helped illuminate targets over Berlin for the main force of over 380 bombers. On its return from Berlin, Fordyce's Lancaster crashed in Norfolk, England. Three of the seven crew members perished, including 23-year-old pilot Gordon Fordyce.

Curtis Goring, 28, attained the rank of WOII-Air Gunner and joined the RCAF #405 City of Vancouver Squadron of Pathfinder Force.

On September 1, 1943, his Halifax was shot down by a night fighter near Berlin and although his body was never recovered, five members of his crew survived and became prisoners of war.

Charles Arthur Nash, who went by “Art”, was an amicable, fun loving person. His sisters recall how he gave them rides on his motorcycle. They'd be sitting in the sidecar as he sped up and down Sarnia's streets.

On the night of June 11/12, 1943, two months after joining RAF #83 Squadron of Pathfinder Force, Art, 24, was the WOII-Air Gunner aboard a Lancaster. During an operation targeting Munster, Germany, his Lancaster failed to return and probably crashed into the North Sea. Art's aircraft and body were never found, but the corpses of two crew members washed ashore. The Germans recovered the bodies and buried them in Holland.

In Sarnia, parents Albert and Lillian Nash were devastated and rarely mentioned their only son. Albert passed away in May 1945, less than two years after Art died. His daughter, Alice, always maintained that her father had died from a broken heart.

Until she passed away in 1979, Lillian vividly remembered the day the family saw a young cyclist ride up to their home holding a telegram. Albert refused to answer the door, but Lillian did, even though she was sure the telegram contained the grim news of her son's death.

For over three decades, if a family member ever asked her about Art, she became teary-eyed and said only, “He never came home.”

The names of the three brave Pathfinder Force members from Sarnia are inscribed on the cenotaph in Veterans Park.