Tom Slater & Tom St. Amand

This July 5th will mark the 100th anniversary of Canada adopting the poppy as the flower of remembrance.

Each November, Sarnia-Lambton residents pin on a poppy with pride and patriotism, and over the past century have donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to support local veterans and related causes.

For the anniversary, the Royal Canadian Legion is producing a commemorative poppy that resembles the original silk flowers made by war widows and orphans in war-ravaged France, along with a card to recognize those most responsible for the now century-old tradition: John McCrae and Anna Guerin.

The remarkable story begins during the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium, which raged from April 22 to May 25, 1915. When it was over 2,100 Canadian troops lay dead, including Sarnians Harry Bury, Roy Iliffe, and Thomas Powell.

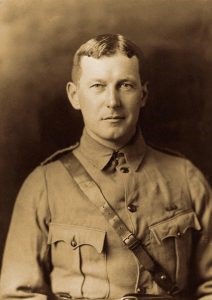

Near the medieval town, on May 2, an exhausted Canadian medical officer sat down to write a poem, pausing to stare at rows of white crosses and the freshly dug grave of his good friend Alexis Helmer.

The next day, Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae finished the poem, “In Flanders Fields.” It describes poppies blowing “Between the crosses, row on row” and ends with the lines, “We shall not sleep, though poppies grow/In Flanders fields.”

It resonated with soldiers immediately.

The battlefields of the First World War were wastelands, yet the tenacious poppy continued to blossom in the pockmarked fields and roadsides of France, Belgium, and Gallipoli. Soldiers noted how they covered the graves of fallen comrades, their brilliant red incongruous but beautiful in the bleak landscape. In soldier folklore, the red arose from the spilled blood of comrades.

McCrae wrote out his poem by hand for soldiers who requested it, and some mailed poppies home. After Punch magazine published “In Flanders Fields” that December it became the war’s best-known poem.

John McCrae, 45, continued to tend to the wounded until he himself died in France of pneumonia. The Guelph, Ont. native never knew how his poppies would become a symbol for millions worldwide.

The First World War ended in November 1918, but “In Flanders Fields” continued to inspire others. One was Madame Anna Guerin of France, who campaigned tirelessly for Allied nations to adopt a memorial poppy.

Known as “The Poppy Lady of France,” she envisioned poppies being distributed on Armistice Day (now Remembrance Day) as a fitting symbol to commemorate the dead and support struggling veterans.

On July 4, 1921, Guerin proposed her idea to the national conference of the Great War Veterans Association (predecessor of the Royal Canadian Legion) in Thunder Bay, Ont.

The following day, Canada became the first Commonwealth nation to adopt the poppy as its national flower of Remembrance, setting an important precedent for other countries.

In 1926, Sarnia’s Great War Veterans Association became the Royal Canadian Legion, Branch 62. Current Poppy Chairperson Laurie Chafe said about 40,000 poppies are distributed to local residents each November, raising $65,000 to $70,000 annually.

Poppy sales support local Canadian Armed Forces veterans and RCMP and their families with food, heating, prescription medication, and housing.

Despite the pandemic and the loss of in-person contact last November, local residents continued to pitch in with another $65,000 in proceeds, said Branch 62 President Les Jones.

“Last year we could only distribute the poppy boxes throughout Sarnia. We were pleased when businesses and organizations called us for a donation box.”

Tom Slater and Tom St. Amand are retired teachers in Sarnia and regular contributors to The Journal.