Phil Egan

I was 15 when the phone call came from my best friend, James O’Rourke.

“Turn on the TV,” he urged. “It sounds like there’s gonna’ be a war!”

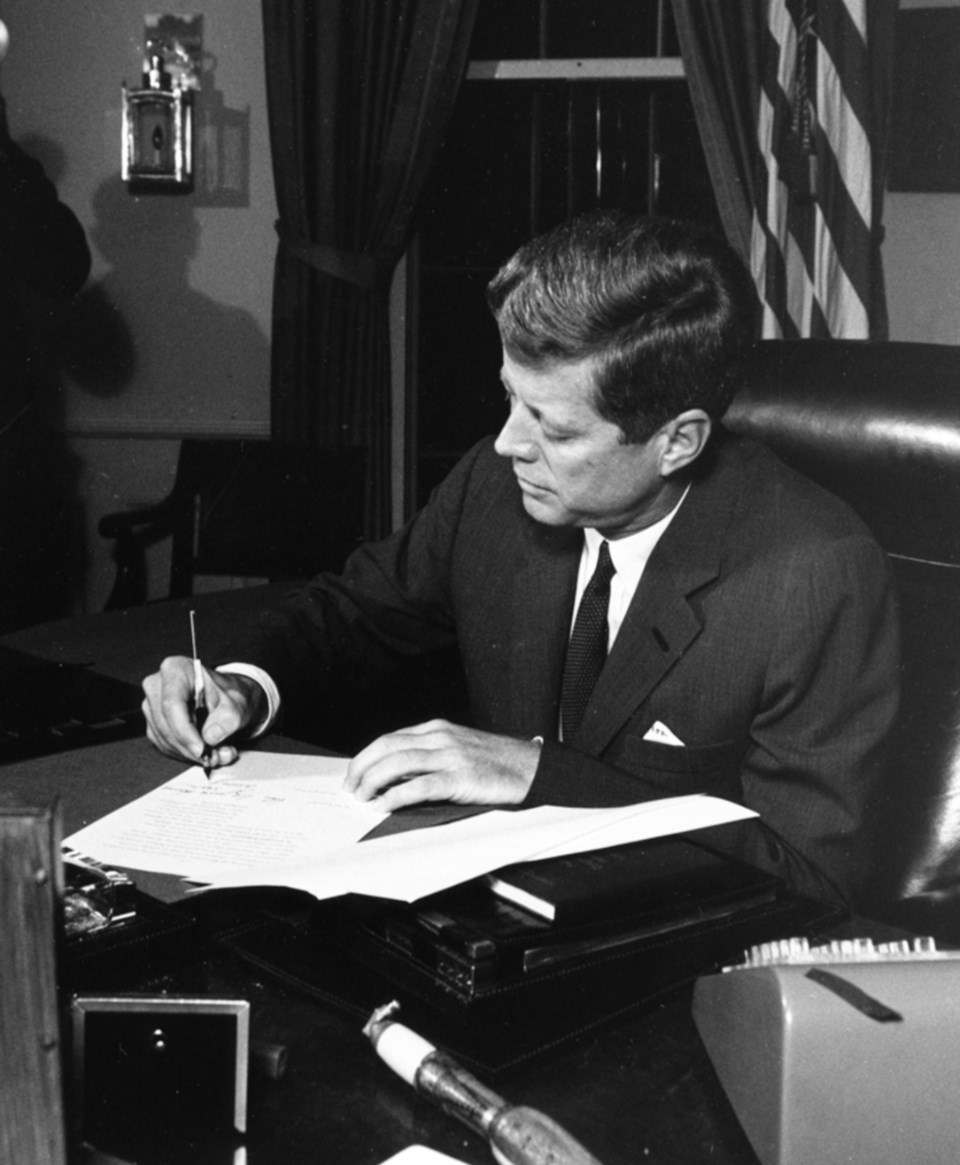

Like most families in 1962 we had a single small black and white television. It brought in three Detroit channels so finding a sombre-looking John F. Kennedy, the U.S. president, wasn’t hard.

It was Oct. 22nd – the first public disclosure of a panic known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On the previous Tuesday, at 8:45 a.m., Kennedy had learned from U-2 spy planes flying over Cuba that six Soviet medium-range ballistic missile sites and twenty-one IL-28 bombers were now stationed just 90 minutes from the U.S. heartland.

The people who had threatened to “bury” the West were now knocking at the door.

The U.S. military began plans to bomb the missile sites followed by a full-scale invasion of Cuba, and Kennedy went on air to warn the Soviets and to announce a naval “quarantine” of Cuba.

Russian ships, currently steaming towards Cuba, possibly with nuclear warheads, would be turned back or sunk if they defied the blockade.

Even now, 60 years later, I can recall how the president’s words sent a chill down my spine.

“It shall be the policy of this nation,” Kennedy said, “to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba, against any nation in this hemisphere, as an attack by the Soviet Union against the United States, calling for a full retaliatory response against the Soviet Union.”

In schools across Sarnia over the following days, teachers who had yet to fathom the destructive power of a nuclear explosion, drilled students in escaping classrooms, hiding under desks, and huddling in window-less corridors.

At St. Patrick’s High School, which I attended, the nuns chose to deal with the threat in a different way.

“We need you to pray for our president,” Sister Maureen told us.

That raised some eyebrows.

“What do you mean, OUR president?” someone ventured.

Sister Maureen didn’t seem to understand the question. An Irish Catholic president, to a Catholic school named for the patron saint of Ireland and the home of the Fighting Irish – why, of course, in her eyes, Kennedy was “our president.”

The Russians eventually backed down, but those were scary days. Schoolboys in the ‘50s had grown up with rumours of Communist bombers targeting Sarnia to take out the Chemical Valley and St. Clair Tunnel.

We already considered ourselves a target. So those of us who lived through them will never forget those last days of October 1962.

Phil Egan is editor-in-chief of the Sarnia Historical Society. Got an interesting tale? Contact him at [email protected]