As part of our Sarnia Remembers series — now in its eighth year — The Journal is publishing a series of stories this week, honouring veterans and fallen soldiers from Sarnia-Lambton.

By Tom St. Amand and Tom Slater

By Tom St. Amand and Tom Slater

For Art and Florrie Graham, the timing of events in August 1941 couldn't have been worse.

Lloyd, their youngest son, 19, was determined to join his two older brothers, Bill and Jack, in serving during WWII. Art, a WWI veteran, and Florrie didn't object to Lloyd enlisting, but Florrie wanted Lloyd to serve in the navy.

Lloyd, though, had other ideas. He worked at a machine shop, was mechanically minded, and one of his hobbies was building model airplanes. The RCAF, Lloyd reasoned, was a natural fit.

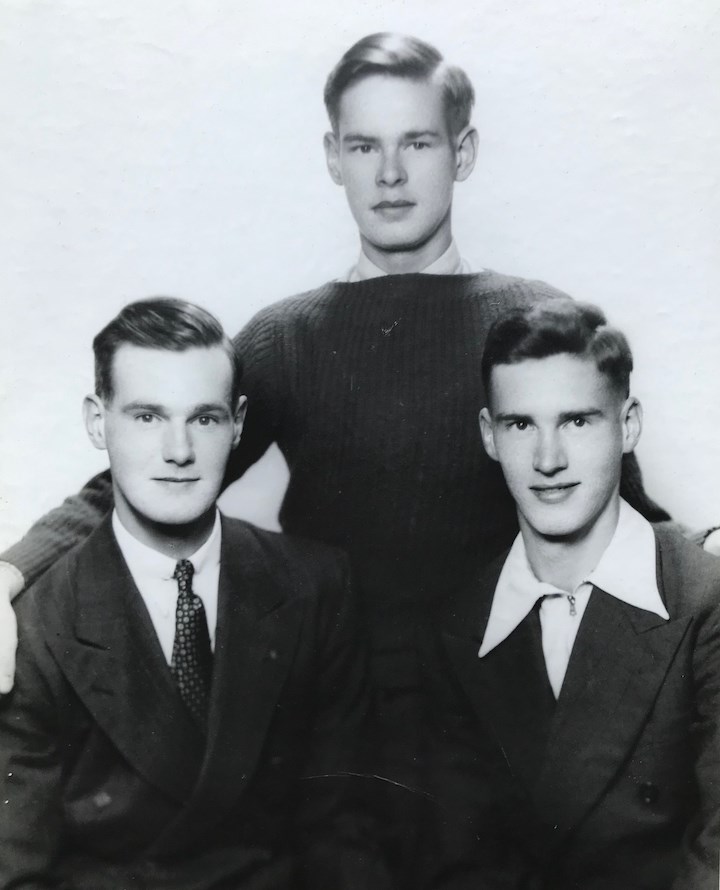

So, on August 12, 1941, a week before Bill and Jack participated in the Dieppe Raid with the Essex Scottish Regiment, Lloyd quit his job and enlisted with the RCAF. A week after the disastrous Dieppe Raid, the August 25 edition of a Sarnia paper featured a photo of the three Graham brothers with the headline “Will Follow His Two Brothers Into Canadian Uniform.”

The newspaper article then listed the fate of several local soldiers at Dieppe.

The news was not promising, and Art and Florrie could only hope and pray. Six weeks later, they finally heard what happened to Bill and Jack.

On October 12, Thanksgiving Day, while Lloyd was busy training to be a tail gunner, telegrams and letters arrived at their home on North Vidal Street. Thank God both their boys were alive. Jack had been captured at Dieppe and was now imprisoned at Stalag VIII-B, the largest German POW camp of WWII. Bill had made it safely back to England, but confessed that the mental anguish about Dieppe was taking its toll: most nights in his sleep he relived the nightmare of the disastrous mission at Dieppe.

With their two older sons confirmed to be alive, the Grahams turned their attention to Lloyd.

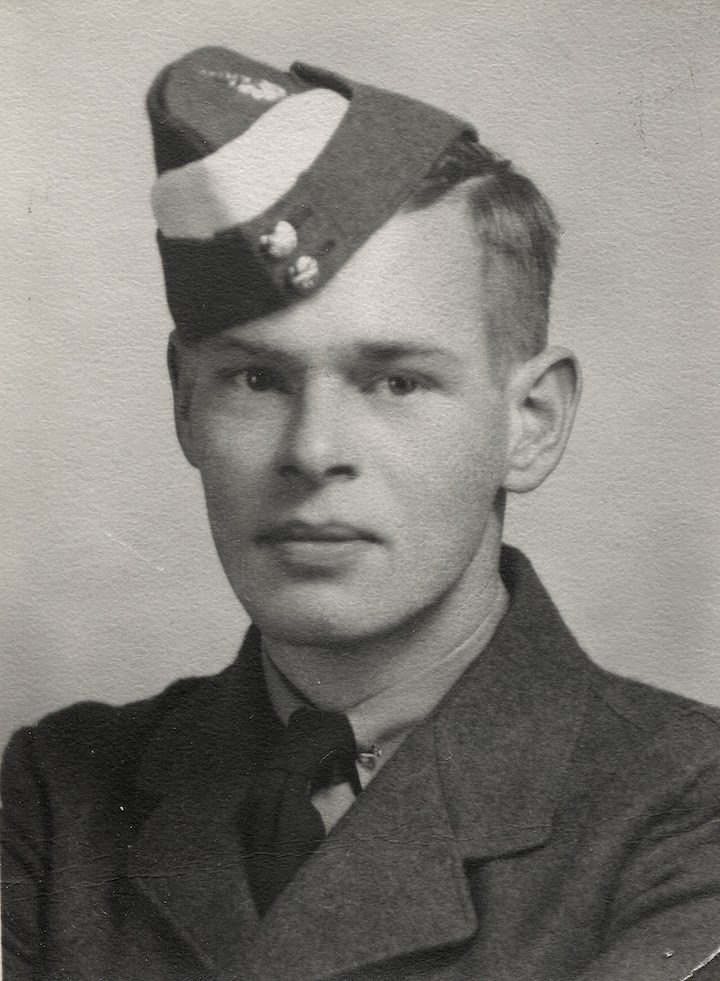

His RCAF training in Canada completed, Lloyd had embarked overseas on March 25, 1944, where he continued his air training in the “heavy” bombers. Lloyd was popular with his fellow airmen, who admired his high standard of excellence as a wireless operator and appreciated his personable nature. In early November 1944, he became a member of RCAF #419 Moose Squadron, part of Bomber Command.

A month later, in late afternoon on Wednesday, December 6, 1944, Lloyd's Lancaster bomber KB779 left RAF Middleton, St. George Airbase in northeast England with 15 other Lancasters of Moose Squadron. If all went well, a fleet of 453 bombers would arrive in the darkness at Osnabruk, Germany, drop their payloads on the city's airfield and railway yards, and return to their bases by 2240 hours.

The seven crew members aboard KB779 had been together since November. This was their seventh mission and they knew one another well and trusted each man to do his job. They had complete confidence in their pilot, 20-year-old Nova Scotian, Bruce Hyndman, 20, who had saved them from certain death on the previous mission.

On that December 2 sortie, the sub-zero temperatures and horrible weather had hampered operations as bombers flew to Hagen, Germany. The ice on the fuselage of Hyndman's bomber was so built up that the aircraft lost all lift abilities. The crew was helpless as the Lancaster fell from 16,000 feet to an unnerving 3,000 feet before Hyndman regained control. The icing also damaged the aircraft's intercom system and camera and the important DR compass was rendered unserviceable. Using standard compasses, Hyndman got them safely back to base.

Four days later, when they boarded Lancaster KB779 on December 6, the crew noticed they would be flying in similar weather conditions.

Shortly after a routine takeoff at 1640 hours, Lloyd contacted the main base, confirming that they were experiencing no problems. And that was the last time that anyone heard from Lancaster KB779.

What happened to Lloyd and his fellow crew members remains a mystery. When the Lancaster failed to return to base later that evening, Bomber Command personnel waited and speculated.

No one doubted that the Lancaster had landed or crashed. Why and where were the key concerns. The weather during the bombing mission was less than ideal, principally because of the icy-cold temperatures. Perhaps the accumulated ice on the exterior of the plane had caused essential equipment to malfunction. Maybe this time, Bruce Hyndman could not regain control of his bomber as she spiralled downwards.

Perhaps a German night fighter had shot down the Lancaster or maybe it was downed by enemy flak. The best outcome was that all seven airmen survived and were now prisoners of war.

After being informed that Lloyd was missing in action in December 1944, Art and Florrie held out hope that he would be found alive; however, no crew member from Lancaster KB779 or any trace of the doomed bomber has ever been found. In October 1945, five months after VE Day, the Grahams received a letter stating that their beloved Lloyd was “now for official purposes, presumed dead, overseas (Germany).”

Things did not get easier for Art and Florrie Graham. Bill, a husband and father of a baby girl, and a lieutenant with the Essex Scottish Regiment, died in action during the Battle of the Rhineland in Germany. A bomb exploded near him on March 2, 1945, as he led his platoon toward Hochwald Forest. Bill was killed instantly.

Jack survived the war, but carried the weight of his imprisonment for years. When he was freed from captivity on April 16, 1945, Jack walked outside the main gate, his first steps as a free man since Dieppe. The 6' 2” Sarnian weighed 100 pounds.

Lloyd was posthumously awarded the 1939-45 Star, the France and German Star, the Defence Medal, the General Service Medal and the C.V.S.M. Award and Clasp. Twenty-one-year-old Lloyd Graham has no known grave and is memorialized at Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, United Kingdom, Panel 250.

Art and Florrie have passed away as well, but the words of Herodotus, a historian in Ancient Greece, might have haunted them after the war: “In peace, sons bury their fathers. In war, fathers bury their sons.”

St. Amand and Slater are the authors of Valour Remembered: Sarnia-Lambton War Stories, available at The Book Keeper.

For more Sarnia Remembers stories, click here.